If you know how much I love the Old Masters, Leonardo, Rafael, Michaelangelo, Perugino, Lippi, and especially Botticelli, you already understand how I’m enjoying Florence. You can’t walk a block without coming across something that one of these guys had a hand in.It’s paradise and exhaustion.

But I’m also seeing so much art that is not by one of these heavy-hitters, and I hate to say it, but I might be starting to question the absolutist oligarchy of art history that has formed around this group of guys. Maybe Leonardo was not the best ever, maybe some dude you’ve never heard of was just as good….

Does it sound like heresy? It sure feels like heresy.

Alright, there are some things that cannot be disputed. Let’s go through a short list of undeniable facts, as I’ve come to understand them.

1. Michelangelo really IS unrivaled when it comes to sculpture. Every single body he ever carved has so much mass and weight.My favorite example of this is in his famous Pietá in Rome. Christ’s body is heavy in Mary’s arms, and we see this beautifully conveyed in this little detail of Christ’s underarm, where we can clearly see Mary’s hand pressing into the flesh of his side, and raising that area of fatty tissue over the muscle. Just like a real, heavy body would look when someone holds it up.

2. Leonardo is really the master of background shadows.

His extreme use of shadow is unlike anyone’s I’ve seen, and it adds a depth and softness to his figures that not only adds dimension, but an air of mystery. This is the “sfumato” that we hear so much about – “smokiness.” The darkness of the shadows keeps the “softness” aspect from becoming too saccharine, as often happens with Rafael.

3. Botticelli really does know how to paint a beautiful face. I could look at Madonna of the Magnificat forever…

But other than that, I’m really not sure how unrivaled the masters are. First of all, every Renaissance painter I’ve seen still retains that quality of “cartoonishness.” Botticelli is an extreme example of this, as his are some of the most cartoonish of all. That’s not to say they’re not beautiful, but his paintings never come close to breaking the illusion that what you’re looking at is a painting, not real life. It’s like looking at particularly gorgeous anime.

Not to ask the most cliché question ever, but… I’m starting to wonder what makes “good art.” Well, Giorgio Vasari thinks he knows, so let’s start there. Vasari’s most famous contribution to history is his “Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects,” in which he literally just identifies several dozen of the best artists of the Italian Renaissance and provides biographical sketches about each one, in addition to analyzing the quality of their work. In deciding “who is the best,” Vasari’s discussions center around several aspects of the artwork: the harmony of the layout and design, the accuracy of the perspective, the “lifelike” quality of the figures, the vibrancy of the colors, the emotional truth of the faces and bodies, and the context in which it was painted (that is, he holds later artists to higher standards because they have a larger body of quality art to learn from).

Ok, so let’s look at some pictures. This is Michelangelo’s representation of The Holy Family:

Vasari LOVES this picture (not just because he has a serious man-crush on Michalangelo) because of it’s perfect composition, all three of the figures unified by motion and rotating around a single central axis. But the colors are very loud, and the outlines of the figures are almost cartoonish to me – they look like they’re cutouts resting on a separately prepared background. And the shadows are a bit dramatic as well – take a look at the one under the Virgin’s foot… So there’s an example of genius of design, according to Vasari.

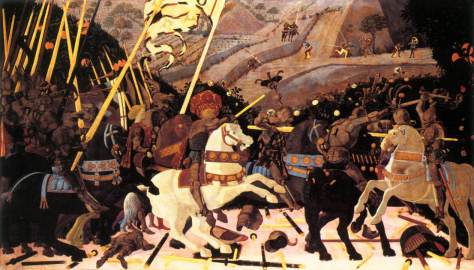

So what about perfect perspective? Paolo Uccello was a painter who, according to Vasari, was completely OCD about his perspectives. This is his most famous work, The Battle of San Romano:

Mid-15th century. Apparently part of the multi-panel work is in the Uffizi, but I don’t remember seeing it…

Apparently this picture is mathematically perfect as far as perspective goes. I won’t even try to parse that, but that’s what Vasari says, so we’ll take his word for it. But perfect perspective does not an artist make: “Although the details of perspective are ingenious… yet if a man pursues them beyond measure he does nothing but waste his time, exhausts his powers… and often transforms his mind’s fertility and readiness into sterility and constraint, and renders his manner… dry and angular, which all comes from a wish to examine things too minutely… very often he becomes solitary, eccentric, melancholy, and poor, a did Paolo Uccello.” Apparently, getting everything technically right does not a true artistic genius make. And I think most of us would agree – good writing is not just perfect grammar, good music is not just following the rules of voice leading, and good acting is not just memorizing lines and blocking. In fact, brilliant art more often than not actually violates these formulaic standards… but I digress.

One aspect that I certainly look for in painting is indeed the lifelike quality of the figures. How alive do they look, how true? Vasari gave two gold medals for lifelike figures: To Rafael, and to Leonardo. Vasari describes how extraordinarily lifelike the Mona Lisa is: “In this head, whoever wished to could see how closely art could imitate nature… the eyes had that lustre and watery sheen which are always seen in life, and around them were all those rosy and pearly tins, as well as the lashes… the eyebrows, through his having shown the manner in which the hairs spring from the flesh, here more close and here more scanty, and curve according to the pores of the skin, could not be more natural. The nose… appeared to be alive. The mouth… seemed, in truth, to be not colors but flesh. In the pit of the throat… could be seen the beating of the pulse.” And he has similar things to say about some works of Rafael. So here is the Mona Lisa:

So according to Vasari (who is writing in the mid-16th century, I should make clear) this portrait is the ultimate expression of naturalism and lifelike representation. But I’ve always had this single enormous problem with most paintings that try to represent a human face: What would that face look like in real life? Like literally, if the portrait came to life this minute, how would the painted face translate into actual human features? For almost all Renaissance art, the disparity between art and life is too great. Even for Mona Lisa, I cannot conjure up an image of a real woman with the features I see in the painting.

But I don’t have this problem for all art, however. For instance, let me show you a few portraits by John Singleton Copley (second half of the 18th century):

These are just a couple examples, and of only one artist, but for each one I feel as if I’m almost looking at a photograph, or a freeze-frame. Each of these has that quality that enables me to imagine that face moving, speaking, having different expressions. As beautifully shaded as Mona Lisa is, and as expressive her smile, to me she looks frozen compared to these. In short, she looks like a painting. A very nice painting, but not a person.

I know putting Copley next to Leonardo is comparing apples to oranges, and I’m wrapping up the discussion prematurely in the interest of space (and your attention span) but it makes me think: Why are the faces of Mona Lisa, or “Lady with an Ermine,” or Botticelli’s Venus so universally praised and instantly recognizable, while I would put money that anyone reading this has probably never seen these particular Copley portraits before?

When I look at some paintings by Tintoretto, Lippi, Botticelli, Leonardo, Perugino, Rafael I have a strange deep feeling inside. It’s like when you fall in love. You feel this unearthly beauty by your heart.

You can’t feel it when you look at a copy, but when you see the original it’s inexpressible.

And when I look at Copley I just see a well-done portrait.

That’s the difference 🙂

That’s very beautiful, Anton! I’m glad you have such a visceral reaction to art, not just checking famous painters off your museum-list or something!